Dark Arts, Light Aircraft

Dr Phillip Judkins and Squadron Leader Mike Dean MBE on the role of autogyros in calibrating Battle of Britain radar stations.

One of the authors’ frequent tasks is fielding queries from television or film production companies, usually from more (or less) engaging media studies interns who are trying to research a military electronics topic in an impossibly compressed timeframe, and have no desire to read other than websites.

Battle of Britain Radar

Top of the list of subjects to film tends to be Battle of Britain radar – we rightly dreaded 2020, the Battle’s 80th anniversary – and apart from the usual ‘Are any of the original scientists or operators still alive?’, a close second question is often ‘We’d like to do a recreation of the Battle of Britain radars, can you help us?’, or ‘Is there an angle that no-one else has tried to show in a TV documentary yet?’.

The answers, of course, are ‘Yes, but very, very, few’, ‘Yes’ and ‘Yes’, but the result might not be what the viewers want. This is because, as Newcomen members may know, Chain Home (CH) radar of Battle of Britain vintage is not at all the concept of radar which viewers, and indeed TV companies, have in mind – an image typified by the Plan Position Indicator (PPI), a map-like style of presentation with the radial time-base sweeping round the screen clockwise.

A-Scopes and Goniometers

Explaining that the Battle of Britain radar display gave only range at first, and if you were skilled, some vague idea of number, by interpreting a jumbled A-scope display – and then going on to explain the operation of the ‘gonio’, first to obtain bearing, and then with a bit of help, height, results in horrified expressions of shock from the researcher. Going further, to explain that British fighters were tracked with the aid of the radio navigation system Pip-squeak and good old direction finding (D/F), and finally that, once over land, Chain Home gave way to the Observer Corps, with all three information feeds going into the Filter Room, one can tell that the TV companies’ mental circuits are in overload!

This is sad, because the full story would allow a number of unsung heroes to be given their rightful due. The GPO engineers, the Observer Corps, and the Filter Room staff, to name but three – plus the operators and mechanics at the Chain Home sites have never really received proper praise for their skill in interpreting the traces on their screens.

Calibrating Chain Home

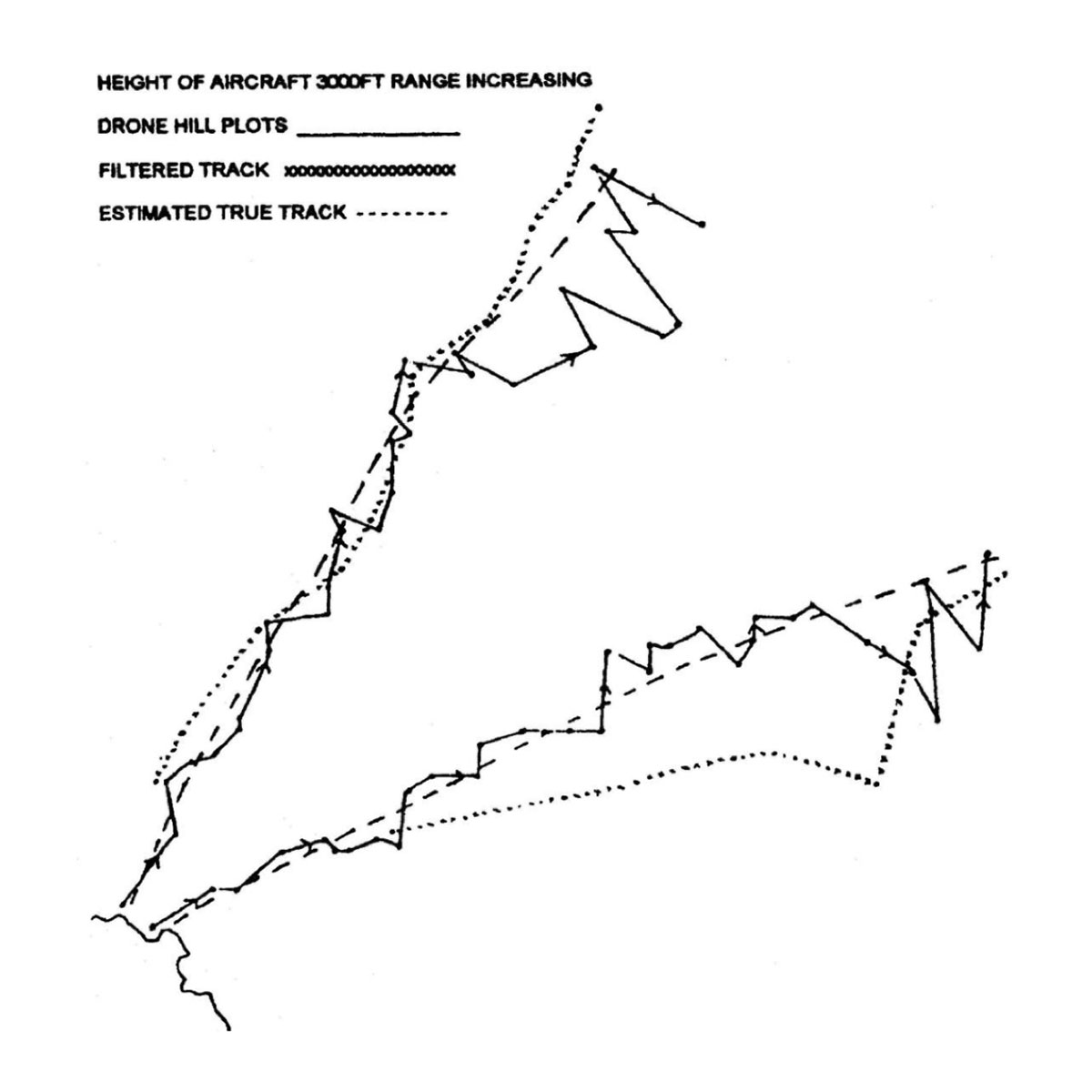

But even before those operators could exercise their skill, another almost completely-forgotten group had practised their own dark magic. These were the calibration staff, without whose efforts the radar stations could give wildly misleading results.

It seems to us, easy for a TV company to explain that each of the Chain Home stations had different characteristics, often due to aerial problems, for no doubt many TV viewers twiddle their aerials, wondering why theirs has to be a little different to next-door’s to get a good signal. This (we say to TV researchers) is similar to the dark art of calibration, where each of the radar stations separately had to take readings on a target flying at a known distance, bearing and height, and use the results to modify future readings to find the true target position.

Unpublished National Archives memoranda show that on 1 August 1940, Ventnor, Poling and Pevensey (half the South Coast radars) could not give accurate bearings, while Ventnor, Poling and the key Dover radar could not give accurate height. To define “inaccurate”, bearings could be as much as 20 degrees wrong, or as much as 17 miles at a 50 mile range!One big operational problem was that while calibration was being performed, the radar had to be taken out of action, so a gap appeared in Britain’s defences; calibration was always performed under pressure.

Another problem was how to fly targets of known distances, heights and bearings from each radar station without using up every trained pilot in Fighter Command!

One solution was to try balloons, with small transmitters on their anchoring cables; since the Chain Home stations looked seawards, the balloons had to fly from boats. Bawdsey scientists chartered the boats “Ialine” and the “Recovery of Leith” as tenders on whose balloons the Chain Home stations might take bearings, and calibrate their equipment. However, coastal winds often blew the balloons out of position, and Fighter Command HQ pronounced them as slow, cumbersome and seriously inaccurate; plus the fact that manning static boats in the Channel during the Battle of Britain would hardly have been a sought-after duty!

Enter the Autogyro

Enter the autogyro, one of the strangest weapons in the RAF’s Battle of Britain armoury!

The autogyro’s ability to keep position at different heights made it ideal for carrying out calibration, and skilled fighter pilots were not required – indeed, as one of the popular songs of time implies, autogyro pilots were regarded so little as not to wear “wings” at all:

“Oh, I fly an auto-gyro, but I may not have my wings,

It’s a pity – it’s a pity, for they’re complicated things,

Like a tipsy daddy-long-legs, or a May Bug, rather drunk,

Though I know their wayward nature, and have learnt there’s naught to funk,

And I teeter madly skyward, caring nix for what Fortune brings,

For I love my auto-gyro, though I may not have my wings”.

The Avro Rota carried out azimuth calibration of the Chain Home stations, typically by flying in a tight circle or flying very slowly into a head wind (strictly speak they could not hover), in turn over each of 12 chosen locations. There are several UK survivors at Duxford, the Science Museum, and as components, with the Helicopter Museum in Weston-super-Mare.

Reggie Brie

An Air Ministry Conference in November 1939 resulted in a six-month contract for Cierva to provide the civilian Reggie Brie’s services to set up and run radar calibration by autogyro. Three Cierva C.30s were ferried to Hendon and on 1st December 1939, attached to 24 Squadron. Under scientist Dr Kinsey, special equipment was installed, and the Dover Chain Home radar calibrated. The concept proven, within two months Reggie Brie personally calibrated seven Chain Home radars from Ventnor, Isle of Wight to Netherbutton, Orkneys. By January 1941, the force had become the nine-strong Rota Calibration Flight, Duxford, Brie himself joining the RAF as an Acting Flying Officer on 5th May 1940 but rising to Acting Squadron Leader by 7th July! Alan Marsh was to take over the Duxford calibration flight after Brie.

An interview with Reggie Brie can be listened to at www.aerosociety.com

Constant Re-Calibration

The autogyros were sorely needed, for calibration was not a “once-for-all-time” exercise. Newcomen members might guess that it needed to be repeated every time frequent adjustments were made to the equipment, or to the aerial system and its feeders. Add to this, the scientists wanting to try new circuitry almost every day, and maintenance by inexperienced technicians – each time demanding yet more calibration – and the burden placed on Brie’s small team can be imagined.

By 8th August 1940, as the Battle of Britain was raging, calibration had become such a headache that Dowding personally chaired a review. Because a station being re-calibrated left a gap in coverage, Dowding insisted that his HQ in future authorise each one. He also authorised more calibration aircraft, decided that some had to be armed, and forbade autogyro use where they were exposed to enemy aircraft. This was as well – an autogyro had to make itself scarce when German bombers attacked the Ventnor radar!

Someday, a TV company might like to make the true story of Battle of Britain radar and its crop of unsung heroes, including the autogyros; we live in hope . . .

With thanks to the Defence Electronics History Society (DEHS) for allowing us to publish this item.

Are you a member of the Newcomen Society?

Having just celebrated its Centenary Year, the society has published over a 1000 papers in The Journal – an invaluable archive of original research material published twice a year, covering all aspects of engineering from ancient times to the present, plus available to browse and download in our FREE TO MEMBERS Archive.

Full Membership includes:

- Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology (two issues, one volume per year)

- Printed and/or PDF versions of LINKS, Newcomens’ newsletter (published 4 times a year)

- Free access and download facilities to the Society’s Archive of past papers back to 1920 (The Journal)

- Membership of local branches and subject groups

- Access to the website’s Member Area offering access to research sources & access to other members (subject to privacy permissions)

- Attendance at summer meetings, conferences, lectures and study days.

I have just been forwarded your newsletter re radar by a friend who is a member of the Newcomen Society. My father, Bruce Samways, was a Cambridge graduate and recruited into radar During World War 2, , working in Worth Matravers , Skendleby, Aden, Egypt and finally Ceylon where he was responsible for erecting radar stations including Trincomalee. During lockdown I have just finished typing his manuscript about his journey written before he died in 1987. I have also added a number of his illustrations/photographs. I am in the process of trying to publish these memoirs. I am still looking for someone who might be prepared to write a foreword.

Rosemary,

the Defence Electronics History Society is a remarkable group with a strong interest in the history of radar among many, many other issues. Their website is given at the end of the piece on calibration – http://www.dehs.org.uk. They have a remarkable publication record with both an extensive monthly electronic Newsletter and a quarterly printed journal called Transmission Lines. I am sure they would be delighted to hear from you, not least because they have had already had an approach from the son of another Cambridge graduate who was also recruited to radar work during the Second World War in similar circumstances.

Jonathan Aylen

President, Newcomen Society

Rosemary,

Delighted that Mike Dean and I could help add a little more information to your father’s story, and looking forward to providing a Foreword to his important memoir.

During lockdown, I have been re-reading some books on the Battle of Britain. While all highlight the importance to the conduct of the battle of the Chain Home stations, none makes reference to the frequent need for calibration and this note redresses that balance. Perhaps it can serve as a reminder that creating a novel system or machine is one thing but getting it to work and keeping it working may be quite another story. Also, as an ex-Avro men, I am interested to learn more about the wartime service rendered by some of the 66 Cierva C.30As built under licence by Avro from 1934 onwards.

Could I add that Phil, thanks to some encouragement from members of Newcomen, asking about the layout of the aerials in the Chain Home System, did a very good review in the November 2015 DFHS Electronic Newsletter. Perhaps quite deliberately because of secrecy, or simply because the aerial cables were too thin to show up, there are no photograph of the set up. Essentially a supporting cable is strung between two of the towers and from these hang two cables. A number of horizontal wires, which are the aerials proper, are set a few feet apart, run between the vertical cables.

That is the basic arrangement although there are additional features, easy to see in the diagram that Phil supplied, but impossible to describe in words. It is completely different to in design and operation to how modern radars operate. It is now wonder that German technocrats could not believe we had radar.

Many thanks for this comment, and for the encouragement – I am happy to provide Newcomen Society members with the November 2015 issue of the DEHS monthly e-Newsletter eDEN referenced for their private study and research; please contact me, DR Phil Judkins, at info@dehs.org.uk

In early 1941, I was living in Puddletown Dorset, as an evacuee from London. My sister and I had been sent there following the death of my father, who had been on duty in the Auxiliary Fire Service in October 1940. My memories of that period are somewhat fragmented, but very clear, even though I was only 4.5 years old.

One day whilst playing in the field outside Home Cottage, I noticed what I thought was a biplane flying slowly a short distance away. As it turned slightly, I saw that it had no wings, which struck me as quite novel. This incident stayed with me for years, although I never made any effort to learn more.

It wasn’t until much later in 1955, during my National Service in the RAF as a Ground Radar operator, that the mystery was solved. During my training we were given a short history of the RAF, and of course the development and introduction of the Chain Home radar installations. So it was apparent, at last, that I had seen one of the Autogiros probably carrying out the calibration of the nearest Radar station, which would have been Ventnor. This was the only station that was temporarily put out of action during the Luftwaffe attacks.

I take a long time, but I get there in the end. 26/01/25.